https://arquebus.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Picture-1-3.png

323

473

Rohan Harvey

https://arquebus.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Asset-1arquebus_logo.svg

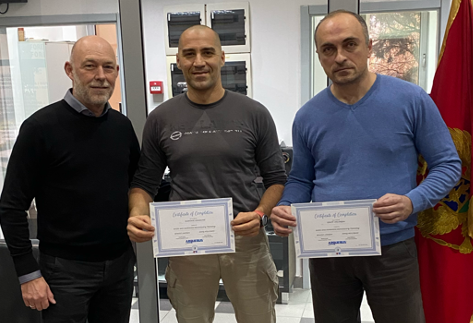

Rohan Harvey2025-02-10 10:04:322025-02-10 15:23:07Arquebus Delivers Ballistic Examination Training in Montenegro

https://arquebus.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/Picture-1-3.png

323

473

Rohan Harvey

https://arquebus.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Asset-1arquebus_logo.svg

Rohan Harvey2025-02-10 10:04:322025-02-10 15:23:07Arquebus Delivers Ballistic Examination Training in MontenegroThe criminal misuse of SALW has become increasingly understood as a threat to collective security, with the illicit proliferation of SALW being recognised as a significant enabler for criminal activities such as people and drug trafficking, whilst also engendering a perception of general insecurity which undermines public confidence in national authorities’ ability to secure populations (SOCTA, 2021).

Partly exacerbated by the growing interconnectedness and organisational complexity of globalisation processes, the proliferation of SALW to non-state actors presents a unique threat to security by subverting the state’s legitimate monopoly on the use of force. SALW security threats are complex, insofar as that multiple criminals, militants or terrorists could misuse a firearm numerous times within a jurisdiction before it is trafficked and then misused again elsewhere (SEESAC, 2017). Therefore, a diverse assortment of expertise across the legislature, the judiciary, law enforcement agencies (LEAs) and forensics is required to meet the complex and dynamic threat posed by SALW misuse.

Following the Paris and Brussels terror attacks, this security threat was brought into sharp focus, motivating the development of the EU Action Plan 2020-25 in 2018. The action plan proposes the development of National Firearms Focal Points (FFPs) for each EU Member State with the aim of “… improving the intelligence picture concerning the use of criminally held firearms and illicit trafficking activities” (Bowen & Poole, 2016). Since then, the action plan has been supplemented by the European Firearms Experts’ (EFE) NFFP Best Practices Guidelines (2018), and the 10726/21 Council Conclusions on the Implementation of Firearms Focal Points.

What is a FFP?

The first FFP in Europe was launched in 2008 with the UK’s establishment of the National Ballistic Intelligence Service (NABIS). Arquebus’ CEO Paul James was the programme manager responsible for overseeing the development and operational activity of NABIS between 2006 and 2012. NABIS was designed to leverage developments in forensic technology such as automated ballistic identification systems (ABIS) and utilise fast-time intelligence techniques to provide:

- Comprehensive, up to date intelligence on firearms and ballistic intelligence.

- Strategic intelligence assessments which aids investigations and operations targeting firearms criminality.

- Recommendations to divert and prevent firearms criminality.

- International firearms tracing services.

- A point of contact and centre of expertise on firearms for national, regional and international partners.

Crucially, the FFP model is not ‘one size fits all’, being adaptable to suit the local security context. For example, an FFP might be a centralised national service such as NABIS, or a ‘virtual’ FFP which utilises a single point of contact to coordinate multiple law enforcement services to operate as an NFFP. Future models might act as regional FFPs, which cover a geographically disparate yet socio-economically interconnected regions.

Added Value

FFPs add value through the development of ‘big picture’ intelligence (Arquebus, 2020) which generates investigative opportunities. The capabilities and intelligence provided by NABIS has empowered UK law enforcement to address street-level violence, Organised Criminal Gangs, Urban Street Gangs and illegal firearms supply, resulting in a 50% reduction in UK firearms crime in the first six years of its existence. In recent years, the efforts of dedicated ‘Gang and Gun Crime’ units in Greater Manchester, London, and Merseyside, combined with the capabilities and intelligence provided by NABIS has enabled law enforcement to address both street-level violence and “… organised criminal gangs, urban street gangs and illegal firearms supply” (Holtom et al., 2018).

This is possible through the recovery of firearms, ballistic material and other associated materials used in crimes and discharges, and its processing and analysis by NABIS, which allows UK law enforcement to create ‘inferred firearms’ to better understand the dynamics of the firearms criminality in each police force area as well as the wider intelligence picture (Holtom et al., 2018). This ‘investigate the gun’ approach, which is made possible through the UK’s NFFP, exploits information through fast-time intelligence to level the playing field against criminals operating in a security environment that is ever-evolving.

Issues With the FFP Model

Despite the benefits, the effectiveness of the FFP model is hindered by gaps in collective security implementation. For example, failures to harmonise legislation regionally can leave legal loopholes liable to exploitation, such as easily convertible Turkish Zoraki alarm pistols which are trafficked into EU and then converted for lethal purpose (Florquin & King, 2018). Likewise, lack of harmonisation regarding SALW information collection and exchange systems, such as failure to utilise INTERPOL’s iARMS system, or by failing to harmoinse firearms registration and licensing systems at a regional level, can negatively impact FFPs’ firearms tracing capability.

Furthermore, the FFP model is ineffective if the system is incorrectly implemented or underutilised. For instance, when the FFP model is performatively implemented to satisfy meta-governance initiatives. Multiple factors might contribute to performative implementation, such as a lack of political will, technical skills or necessary resources. Performative FFP implementation produces FFPs which are unable to produce intelligence which aids proactive security, resulting in a reactive security approach which satisfies a narrow focus upon the establishment of an FFP to fulfil political commitments, rather than to maximise positive social outcome.

In the case of the EU, efforts are being made to prevent performative implementation. For example, through research projects which evaluate the establishment of NFFPs such as FOCALSF.

Yet, is this going far enough? As with all collective security efforts, politics is inescapable. Therefore, the success of NFFPs in Europe will ultimately be contingent on a delicate balance between proactive security approaches, constructive evaluation and the recognition of political sensitivities.

Conclusion

Although the FFP model has seen growing implementation and success within Europe, FFPs do not represent a quick fix for the issue of SALW misuse. Collective security in an increasingly interconnected and complex world requires a continued and sustained effort to follow (and establish new) good practice to meet a continuously evolving threat.